The District Commissioner

Addendum 20: Ivan Champion

Additional information for Chapter 5 - Getting away from trouble by sea and Chapter 6 - Surviving the Japanese invasion

Wikipedia at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivan_Champion states that “Ivan Francis Champion OBE was an Australian public servant in Papua New Guinea. He served as a member of the Legislative Council between 1951 and 1963 alongside his brother Claude Champion. After becoming Senior Commissioner of the Land Titles Commission in 1963, he retired the following year. He then became commander of the ‘Laurabada’ again, now a civil ship, and took up contracts surveying the coasts of Australia and Bangladesh. He died aged 85 in 1989 in Canberra”.

Ivan’s exploratory work was recognised by the award of the Gill Memorial Medal by the Royal Geographical Society in 1938 and the John Lewis Gold Medal in 1951. He was appointed an OBE in 1953.

Ivan Champion was the godfather of the youngest daughter (Diane) of David and Alison Marsh.

The photo is of the Conference of District Officers in Port Moresby in 1947 is from the Jack Keith Murray Collection, University of Queensland.

The Officers identified in the photo are, per Arthur Smedley

Back Row : George Greathead, WJ (Jack) Reid, CT (Clarrie) Healy, Raleigh Farlow, LJ (Jim) O’Malley

Middle Row : JR (Reg) Rigby, Charles Bates, John Foldi, William Sansom, MJ (Mick) Healy, William H Thompson

Front Row, seated : Horace (Horrie) Niall, Oliver Atkinson, Ivan Champion, Administrator Col JK (Jack) Murray, JH (Bert) Jones & JK (Keith) McCarthy

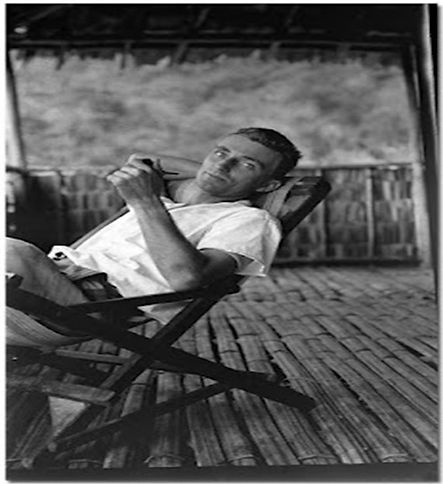

The following is an extract from the article dated 6 July, 2015 “Retrospective: My Grandfather Ivan Champion” written by Ross Plant sourced online 18 September, 2021 at sawtybt.blogspot.com/2015/07/retrospective-my-grandfather-ivan.html.

Mr Plant has kindly allowed his words and his grandfather’s photos which follow to be included in this addendum to our book.

“Firstly, a little background to my story about my Grandfather. I spent the first thirteen years of my life living in Port Moresby in Papua and New Guinea.

I have spent a considerable amount of time scanning negatives that my Grandfather took during the 1920's. Over the past 95 years these negatives have remained in the bottom of suitcases and storage boxes and not stored in ideal conditions. I have tried over the past eight months to bring them back to their original condition using Adobe Photoshop and Lightroom. The most remarkable thing about these negatives is that they were taken using a Kodak Box Brownie and the negatives were produced using river water in the wilds of New Guinea….

My Grandfather was born in Port Moresby in 1904 and at the age of ten attended the Manly Public School in NSW. He finished his schooling at the Southport School in Queensland before returning to Papua in 1923 as a Patrol Officer.

In 1926 the Administrator Sir Hubert Murray asked two Patrol Officers to try to cross New Guinea at its widest point, from the source of the Fly River in the south to the head of the Sepik in the north and follow this river to its mouth.

The Patrol Officers were

Charles Karius pictured here

and Ivan Champion.

They took with them twelve Papuan policeman and forty carriers. Each carrier carried a load of forty pounds which included items like bags of rice, axes, knives, tobacco and salt that they may be able to use for trading.

In December 1926 they were transported upstream by the Government ketch “Elevala” 500 miles from the mouth of the Fly River to the Alice River (also known as the Ok Tedi River) from where they would set out.

Two days later twenty seven of the carriers deserted, terrified by the eerie surroundings and the thought of being eaten by cannibals. Several of the police intercepted them and brought them back. The party penetrated the jungle for 100 miles before they were confronted by a limestone barrier rising to over 2,000 feet. They built two rafts and drifted back down the river taking them just thirty minutes to return to camp whereas the journey on foot had taken them two days.

At this point Karius decided he would take half the police and head in a north east direction to try and find the Sepik and that my grandfather should take the remaining police and carriers back to Daru at the mouth of the Fly River.

My Grandfather however decided he would explore the mountains to the north-west before returning. He had taught himself navigation and always carried a sextant with him, he told Karius he was heading in the wrong direction. This decision was the turning point for the expedition. My Grandfather met friendly natives who led him beneath the limestone walls to the Bol River which was a tributary of the Fly, and then to a native village called Bolovip at an altitude of over 6,500 feet. In those days altitude was measured by boiling water in a Hypsometer. My Grandfather became very friendly with these natives and picked up on their vocabulary by holding up items, saying their names and having them say their name in return.

The Chief Tamsimara, using sign language described a river that flowed to the north. It was the Takin, one of the headwaters of the Sepik. These natives had never seen steel before so my Grandfather presented them with a tomahawk and axe and then showed them how to use them.

They were taro eaters and used stone adzes to ring bark the trees so they could plant their crops. This was the first encounter that they had with white men so they were truly amazed when my Grandfather took of his hat because they thought it was part of his body.

My Grandfather returned to their base-camp to gather supplies but none of the carriers were fit to continue, so he built rafts for the 500 mile journey back to Daru at the mouth of the Fly River.

The rafts often overturned in the rapids, as they made their way past tribes who were at war with each other.

At one point they were confronted by headhunters and cannibals trying to board their rafts but were repelled by the police with their rifles.

Headhunters from the Fly River

A second attempt began in September 1927. They made their way back to Bolivip, and the chief led them over ridges of needle - pointed limestone, through moss covered scrub and across bridges made of vines that were over 40 feet above rapids and bottomless chasms. At an altitude of over 9,000 feet Tamsimara pointed out a great basin surrounded by mountains. In the valley they could make out a wide, muddy and slow moving river.

They started their descent and the countryside echoed with the peculiar frog-croaking warning of the Telefomin people. Armed natives confronted them with drawn bows and arrows, with both men speaking all the peace words they knew and raising their arms in a token of good-will.

The last part of their journey was a nightmare. Their only way forward was to wade through swamps infested by scorpions, lizards and biting insects. To pitch camp they had to build platforms several feet above the stinking swamps bubbling with gases from rotting vegetation infested by scorpions and snakes. Eventually they found trees suitable for making rafts, and drifted towards the mouth of the river. Early one morning they were startled by a rifle shot and as the rafts drifted around a bend in the river here was the “Elevala” which had navigated 500 miles upriver to rescue them. After many months of incredible hardships, New Guinea had now been crossed at its widest point.

My Grandfather had from an early age wanted to join the navy but his poor eyesight put an end to that career. When war broke out he was inducted into the army and became a private in February 1942. Days later he was summoned to the Naval Base and told that he would become a Lieutenant in the Navy. He knew he would fail the medical exam, but Commander Hunt had arranged for the Air Force doctor to pass him, no matter what. It was his navigating and surveying skills that enabled him to achieve his boyhood ambition.

He was given command of the “Laurabada”, which had been the Governor’s yacht. It was fitted with Lewis machine guns and became “HMAS Laurabada”. He would go in under cover of darkness deep in Japanese held territory and rescue troops. One such operation he rescued 150 troops, and set sail into a violent storm which made excellent cover from Japanese warplanes. He was ordered to search for survivors after the Coral Sea battle and found two navy pilots from the lost aircraft carrier, USS Lexington. He also made many voyages taking army units and coast watchers to island posts. He was tasked with piloting Allied ships into Milne Bay and was lucky to escape the Japanese battle fleet as it made its way to a Milne Bay landing.

His most important task once the Japanese were repulsed, was to survey a route from Milne Bay to Oro Bay. After completing this survey he was tasked with piloting Allied ships between these two points before being flown back by the Americans to pilot the next vessel. He piloted the first US Liberty ship into Buna, before coming under command of the Royal Navy towards the end of 1944. He was sent in command of HMS Challenger to survey through Torres Strait so that the British Pacific Fleet could go through at full speed.

He was discharged in October 1945 and returned to Port Moresby before taking over as the District Officer at Daru. His only injury during all his explorations, and during the war was being gored by a wild pig while he was looking through a theodolite on the Admiralty Islands.

In 1951 he was in charge of the relief operations that followed the eruption of Mount Lamington volcano, where over 3,000 Orokaiva people and 35 whites perished.

He left the Public Service in 1964, as Chief Commissioner of the Land Titles Commission before again commanding the “Laurabada” for private owners in Papua and New Guinea waters.

Before he finally retired and moved to Australia, he worked as a surveyor for oil companies along the Great Barrier Reef and was involved in contract work in South East Asia surveying for new harbour developments.

In 1967 my Grandfather was told a story by a Bishop from a Canadian Mission who had visited Bolovip. The steel axe that my Grandfather had given Tamsimara in 1926, was hanging on a wall in pride of place in the men's house. They told the Bishop that it had been given to them by the first white man they had ever seen, being my Grandfather.

In April 1961 a TAA Douglas DC3 was named in his honour (photo below). 2nd photo, my Grandfater on the left.

Distributing carriers rations

Aivara Village camp

Ivivi Village camp

River crossing

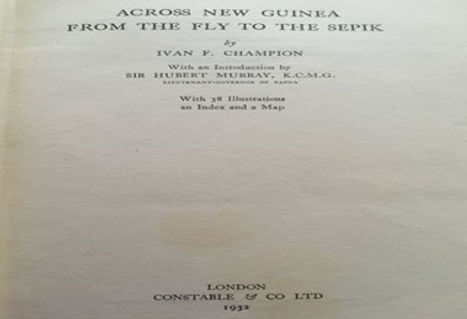

The 2 photos above of the Ivan Champion’s book “Across New Guinea from the Fly to the Sepik” are provided courtesy of Jane Rybarz.